Does Horror Need Things From Beyond Our World?

Horror is a genre I’ve spent much of my time playing. I’ve forced everyone I know to play at least one of these games and raved about each one on here.

This tenure means that I can see common patterns and elements among games. Even horror films fall into the ubiquity of these traps. One in particular that has caught my attention is the almost dependence on supernaturalism in these games.

Two games that are particularly guilty of this are Until Dawn and Outlast. Both stay within the bounds of reality for most of the narrative before bringing wildly zany supernatural enemies for the finale.

In Outlast, the primary antagonist is a brutish patient in the mental institution. Towards the end of the game, however, he is promptly shredded (literally) by the Walrider, a ghostly weirdo.

Until Dawn does something similar: casting off its teen horror film veneer and introducing the Wendigo (Gollum from The Lord of the Rings).

Why do we consistently see supernatural elements in horror games? Of course there are positives, but I’d like to see a few more games about the natural things that terrify us.

The Unknown

What frightens us? Things we don’t understand, things we don’t know. Look at the success of Amnesia: The Dark Descent. A game in which the threat of what might be lurking in the shadows drives the feelings of unease. With Daylight and Phantasmal, we’re seeing a surge of procedurally-generated games to emphasise the power of the unknown.

What better way to put players in an unfamiliar situation than to bring in something that is impossible in real life? I don’t mean thoroughly implausible like being trapped in an abandoned research facility a la Penumbra: Black Plague. I mean literally impossible. Players will have no frame of reference for what logical rules may apply, which can give developers an avenue to really screw with them.

For the most part, it works. There are two times when I would say this falls down: when a game is reliant on this unknown factor and when it breaks suspension of disbelief.

Games naturally obey certain rules. These rules can be set by the developers or simply be extensions of natural laws. Over time, gamers will learn these rules simply because they are subjected to them. If games rely on this gap in a player’s knowledge, it loses its potency as the game goes on or if players simply feed a few deaths to experiment. To see an example of this, look at Dead Space‘s Necromorphs.

For the latter, I’m going back to Outlast. Throughout the game there are certainly allusions to the Walrider in documents the player can collect. But there is little more to suggest this is a tangible enemy and not the ravings of a lunatic (we are in a sanatorium after all). The plight of our protagonist is built so solidly around the fear of this brute and being thoroughly cemented in the natural world that the introduction of this all-powerful ghost creature shatters any investment the player may have in the story. Sure, it jacks up the stakes since the enemy now goes through walls but at this point, who cares?

It Gives Us Access to Unworldly Creatures

Another argument I hear for the supernatural is the ability to include even the most horrific of beasts. Alien as a film (and, therefore, Alien Isolation) would be far less terrifying if it centred around, say, a bear instead of the legendary creation of H.R. Giger.

We see these sorts of inclusions in games all the time. Dead Space, Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, just to name a few. I’m grateful that we seem to be moving past the phase in which developers thought putting zombies in a game made it scary (hello, ZombiU). But the fact remains these monsters’ inclusion is simply a different sense of gore. It appeals to our sense of revulsion more than our sense of fear. There’s no denying I’d hate to run into Pyramid Head in a dark alley. But I’m not necessarily fearful of look.

For me, the truth is we don’t need to be delving so far on every occasion to find the most repulsive beasts imaginable. They have their place, yes, but so does everything else. The Gatherers (Amnesia: The Dark Descent) are some of the most hideous things I’d encountered in horror, but we can keep their creation in the natural realm. They can look as they do while being the results of misguided experiments performed by Alexander of Brennenburg.

I think this is why the short addition to The Dark Descent is one of my favourite horror experiences. Justine is an entirely believable tale. Certainly, her motives are a little far fetched but within the context of the game, I can believe it. The enemies are suitors that Justine has maimed or mistreated in some way. They’re as repulsive as the Gatherers but are worldly. They follow logically from what we’re told. Basile was blinded, imprisoned, and starved by Justine. His reasons for attacking us and looking as he does all make complete sense.

There are conceivable situations that evoke fear

The final point I want to make is this: the world is full of situations that make us fearful. There is little need to go to the well for the stock locations of horror (hospital, sanatorium, abandoned town) or trite profundities.

Horror has a lot of room to grow as a genre of games. With the imminence of consumer-grade virtual reality, the possibilities are only going to get grander. Instead of trying to hammer out a way to squeeze new life out of an old formula, we could be looking to firm up other, neglected areas.

Home invasions is one such situation that can inspire dread. Games we have already are basic extensions of the themes found here (Slender: The Arrival, Five Nights at Freddy’s). Remove the flashy go-faster stripes we’ve put on these games and bring it back to what was terrifying us in the first place: isolation, helplessness, physical threat.

It’s no coincidence that a tectonic shift is happening in horror. Survival horror and psychological horror are drifting further apart. Games that embrace the latter are genuinely scary (Silent Hill: Shattered Memories); whereas games tapping into the former are moving further away from horror roots (The Forest).

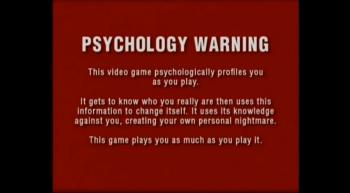

Franchises that can learn from the psychological sciences will be able to look at the roots of fear in humans. They won’t need hellish monsters from beyond to frighten people. They will be reaching people on a much deeper level and doing away with supernaturalism will only help.

I think that horror is not about unknowns, but rather the environment and the situation. Jump scares, gore, blood are physical horror which most people can overcome. When I play horror games I am almost immune to these physical horrors.

We do not fear the unknown, we fear the environment. Ghosts are known to us. We know ghosts can possess people, move objects etc.. yet we fear them. Why? Because of the fear inducing environment they create.Bad Ghosts obsess over playing with humans. Even survival horror can be very scary if the environment induced is scary. Take example of Far Cry 1. You are some guy in an island lost in a research facility, full of mutant experiments. Each and every corner is an enemy and you even have to fight human mercenaries and not just mutants. At some point that environment of loneliness is very scary.

Today’s games do not induce that environment of fear. They are lack luster and depend on jump scares, gore and blood which is common in most movies. Doom franchise probably has more gore, blood and jump scares than all the horror games combined.